Why the Nail-Pressing Penetration Test Does Not Guarantee Lithium Battery Safety?

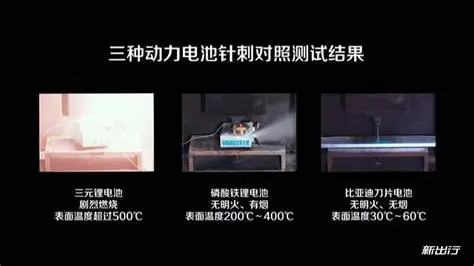

The image below shows the famous BYD Nail Penetration Experiment:

A comparison between High-Capacity NCM (Ternary), High-Capacity LFP (Lithium Iron Phosphate), and Blade LFP Battery. (Detailed videos can be found online.)

We know that whether a lithium battery undergoes Thermal Runaway depends on the severity of the Internal Short Circuit (ISC). Assuming the internal resistance of the lithium cell is Rc:

1). When the internal short circuit resistance is 100~200 Rc, internal heating is noticeable.

2). When the internal short circuit resistance drops to 10~20 Rc, internal heating becomes more severe; if it continues, thermal runaway will occur.

3). When the internal short circuit circuit approaches Rc, the internal short circuit current rises sharply, and thermal runaway erupts.

Of course,

the outbreak of thermal runaway also depends on another factor:

the thermal runaway temperature of the cathode material.

NCM materials are around 200°C, while LFP is around 400°C.

With this knowledge, let’s analyze the BYD nail penetration results:

High-Capacity NCM: The needle penetration depth is sufficient, the internal short circuit is severe, and combined with the lower thermal runaway temperature of NCM, thermal runaway occurs quickly—Reasonable.

High-Capacity LFP: The needle penetration depth is sufficient, and the internal short circuit resistance is similar to the high-capacity NCM. However, the internal resistance of LFP with the same capacity is larger, resulting in a lower actual short-circuit current compared to NCM. The internal temperature does not reach as high as NCM and fails to reach the LFP thermal runaway threshold, resulting only in white smoke.

Blade Battery: Compared to “2”, the Blade Battery has even higher internal resistance, resulting in a smaller short-circuit current. Additionally, the thin blade shape dissipates heat quickly, so the internal temperature rise is minimal. It doesn’t even reach the electrolyte evaporation temperature, so there is not even white smoke.

Does this mean “LFP Batteries” or “Blade Batteries” cannot experience thermal runaway?

The answer is “No”.

Real-world lithium batteries operate as follows:

Multiple batteries connected in series:

Do not underestimate this series connection. When one lithium cell experiences an internal short circuit, if the series circuit is not disconnected, all other batteries will “dump current” into this shorted cell, causing the severity of the internal short circuit to escalate progressively. This can still cause thermal runaway.

Complex Operating Scenarios:

Especially for traction batteries, scenarios include high-current charging, high-current discharging, and high ambient temperatures. High-current operation generates internal heat. If the thermal management system is inefficient or fails, the internal temperature of the lithium battery will rise very quickly.

Real-world ISC differs from Nail Penetration:

Generally, internal short circuits fall into two categories: one is separator cracking leading to a short between cathode and anode materials; the other is Lithium Dendrites or other factors causing a short between positive and negative Current Collectors. These situations are more like “cancer in humans,” involving a gradual growth and deterioration process.

While LFP batteries are indeed more difficult to drive into thermal runaway, it is not impossible, especially when multiple batteries are connected in series.

This is a completely different scenario from a single-cell needle penetration test.

It is undeniable that BYD achieved sales growth by publishing this experiment, but this is due to the inherent characteristics of the LFP material itself, and any other manufacturer can make LFP batteries. As for the Blade Battery, the 96cm long blade is actually not a good design, which we can discuss later.